A recent master thesis project, designed by Alessandro Catania whithin FEDORA's open schooling network, challenged students' imagination at the Baracca Institute of Forlì (Italy). The aeronautic high school, managed by Maura Bernabei, is attended by students who come from all over Italy with dreams of becoming pilots or aircraft engineers. The interdisciplinary activity, at the boundary between arts and science, was developed in collaboration with physics teachers Barbara Teodorani and Andrea Zanchini, and involved an art piece by the argentinian artist Tomàs Saraceno. The artwork, part of a project called "Aerocene", consisted in an aerosolar sculpture that helped students immagine new and more sustainable ways to fly, "reactivating a common imaginary towards an ethical collaboration with the environment and the atmosphere, free from carbon emissions"*.

Get more information reading the article by Alessandro Catania published on the project website: https://aerocene.org/flying-with-aeronatutical-students-in-forli-italia/

*quote from the aerocene website

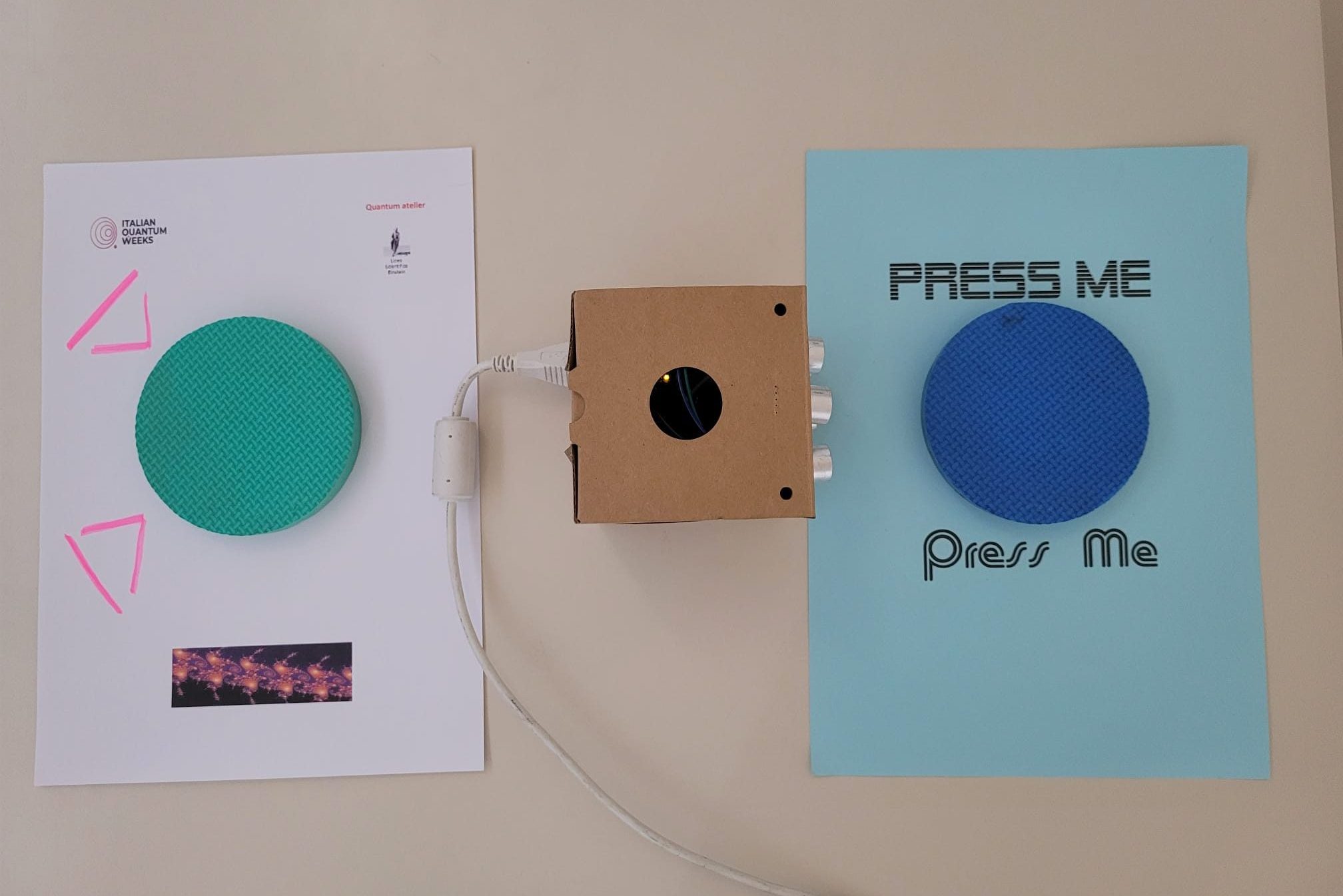

“Quantum atelier” is an art-science laboratorial activity designed by the Bologna open schooling network and implemented at “A. Einstein” high school in Rimini (Italy).

As mentioned in the previous post, at the beginning of its journey FEDORA established three open schooling networks in three specific locations: Bologna, Oxford and Helsinki. Since then, researchers, teachers, communicators, and other professionals worked together at the design of activities and materials based FEDORA's research principles and results. The activities main aim has been to help young students in developing the skills they need to navigate our modern society by engaging them in future-oriented and society-related scientific issues.

The laboratory was preceded by a course about the Second Quantum Revolution designed by doctoral researcher Sara Satanassi and held in collaboration with three teachers (math, physics and literature/art). The 30 students involved (18-19 years old) were introduced to the basic concepts of Physics theory of information, quantum technologies and their societal impact. Eight of those 30 students concluded their educational path attending the “Quantum Atelier” art-science laboratory and challenging themselves by the production of a conceptual artwork.

As professor Giuseppucci wrote,

“The “Second Quantum Revolution” course tried to focus on how this second revolution deeply affects not only our way of looking at reality but also of being in it, requiring each of us to carry on a personal research that guides firstly our thought and then our language, in its various forms, to build images and visions of reality and self.

New technologies are far from being just tools that impart a simplification to our relationship with life, they actually contribute modifying our modes of perception by structuring a new "reality" which is yet to be understood.

In such a scenario, […] he education system, together with the rethinking of teaching methodologies, feels the need to contribute and stimulate the development of new languages, more suited to the challenge of the present. In fact, a new "reality" should be followed by new words, new images, metaphors and even a new aesthetic. This task falls mainly to scientists, philosophers and artists. However, the contribution that the school can provide is to open 'spaces' for experimenting together with the students, fueling a reflection that stimulates students to imagine new forms of representation of the knowledge they are acquiring.”

During the laboratory students divided themselves into three groups, each of them produced an artwork and a description of it. The latter was put into use during the final art exposition called “Finzioni” (italian for “Fictions”), a peer-to-peer activity, organised to let students present their artworks to the rest of the school.

The three artworks, named “|ψ˃”, “Appearance” and “Maze”, were all characterized by an interactive element, that students intended as a metaphor of the scientist in the act of measurement.

The following video, made by the students, illustrated the exhibition and the artworks.

The interdisciplinary nature of Quantum Atelier led students to learn how to dismantling and reassembling knowledge, trying to find a balance between the scientific and the artistic constraints (i.e. the formal and rigorous physics concept and the aesthetic form) as well as a balance with the limits of realisation based on personal skills. Through this process students learnt to look at knowledge from different points of view, becoming aware of personal framing, and they explored how to manage, reconstruct, and communicate knowledge according to personal taste and their personal identity.

Even if the experiences proved to be personally and collectively effective for personal learning and rethinking of the relationship between art and science, the artworks focused on concepts of the first quantum revolution. That enhanced the need to find new narratives to talk about the contemporary science to make people perceive more deeply the scope of the second revolution.

“Climate change at the museum” is the activity created by the Oxford team within the FEDORA open schooling project. It consisted of a series of workshops with local secondary schools held at the informal teaching space of Oxford University’s Natural History Museum.

As mentioned in the previous post, at the beginning of its journey FEDORA established three open schooling networks in three specific locations: Bologna, Oxford and Helsinki. Since then, researchers, teachers, communicators, and other professionals worked together at the design of activities and materials based FEDORA's research principles and results. The activities main aim has been to help young students in developing the skills they need to navigate our modern society by engaging them in future-oriented and society-related scientific issues.

Embedding the principles of FEDORA, the Oxford Open Schooling Network created “Climate change at the museum”, a workshop designed for Year 12 students (aged 16-17) and focused on enhancing students’ future-oriented skills, active participation and use of new languages in science learning, and interdisciplinary thinking on the specific topic of Climate Change. A special feature of the implementation is that the science learning space is extended to an informal out-of-school learning context. In collaboration with the Natural History Museum of the University of Oxford, the FEDORA team co-designed and co-delivered the workshops with museum educators.

The museum was selected because of its focus and interest in climate change and biodiversity activities, which would serve as the basis of the designed lesson. Students were able to have hands-on experience with the exhibits while also discussing about biodiversity and ecological issues in the museum workshop.

The museum was selected because of its focus and interest in climate change and biodiversity activities, which would serve as the basis of the designed lesson. Students were able to have hands-on experience with the exhibits while also discussing about biodiversity and ecological issues in the museum workshop.

The workshop aimed at guiding students to explore possible future scenarios, emphasising the power of collective and personal actions. Through discussions in small groups and whole class, students related the climate change challenge to the interdisciplinary nature of the topic, so much so in STEM, and how different professional roles contribute to this arena. In this way, students were able to see the interconnections between professions, causes and actions with regard to climate change.

A session of students’ group work followed, during which a set of cards illustrating climate change-related scenarios were introduced. The cards were co-developed with two science teachers and were categorised into ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ or ‘troubled’ future scenarios. This categorisation was based on whether or not actions would be taken to address climate change in the future. During the group discussions, students were encouraged to reflect on the importance of the presented scenarios on a collective, as well as on an individual level.

At the end of the workshops, students shared their ideas about possible future scenarios of our climate, the role of science in creating them, and how teenagers and the public can shape this possible future. Students had very positive reflections after each of the workshops. Interviews and feedback from them and their teachers were collected and showed that the workshops raised their interdisciplinary awareness, or as one of the student put it:

At the end of the workshops, students shared their ideas about possible future scenarios of our climate, the role of science in creating them, and how teenagers and the public can shape this possible future. Students had very positive reflections after each of the workshops. Interviews and feedback from them and their teachers were collected and showed that the workshops raised their interdisciplinary awareness, or as one of the student put it:

"I feel environment can come into anything, such as geography and psychology."

At the same time, students' comments showed as this workshop increased their motivation in dealing with future global challenges:

"I really feel, with us being late in our teen years, everything is down to our responsibility to be able to not only act on our own ways to improve, but to also educate other people. I feel programme like this has definitely helped educate a good number of people. I feel I came out of it learning a lot more and I definitely feel changes will probably be made to what I do as a result of it."

"I’m not sure what I’m going to do in the future, but I feel this [the workshop] has made me want to do something in future because obviously my understanding is going strong through the workshop. And I felt like, I could do things to help out."

FEDORA's first round of activities implementations is concluded!

In the next paragrafs you will discover about “Physics of clouds”, one of the innovative teaching activities created within the FEDORA open schooling project. More posts like this will follow, and each of those will tell you about an activity and the results or hypotheses that came out from it.

During FEDORA’s first year, three open schooling networks were established in three specific locations: Bologna, Oxford and Helsinki. Researchers, teachers, communicators, and other professionals worked together on the design of activities and materials, considering the recommendations that FEDORA produced about its main themes: interdisciplinarity, future and new languages. By fostering engagement with future-oriented and society-related scientific issues, the activities' aim has been to help young students in developing the skills they need to navigate our modern society. FEDORA focused especially on inter-multi-transdisciplinary, linguistic/argumentative, imaginative thinking and so-called future-scaffolding skills.

The 'Physics of clouds' activity was designed by the Bologna open schooling network and implemented over a period of three months at “A. Einstein” high school in Rimini (Italy). It involved a class of 15 years-old students and three teachers: one of physics, one of literature and one of history.

The starting point was the conviction (linked to research results) that it is possible to educate on complex thinking from a young age. The physics of complexity is an interdisciplinary theme, so the challenge was to build a context in which young students could experiment with this theme in an interdisciplinary way. That led to the design of the activity as a creative writing workshop which intertwined the scientific with the narrative language. In practice, students were guided into the process of “translating” scientific content from one language to another by re-conceptualizing, clarifying and enriching the content with personal meaning.

But before going into more details, we should clarify: what do we mean by complex thinking? We mean building a particular way of looking at the world, a conscious way of looking, that involves striving to understand the many dimensions involved in the knowledge, to re-establish links between what is separate, and to be able to think locally without losing sight of the totality.

The activity was structured by intertwining interactive lessons and workshops.

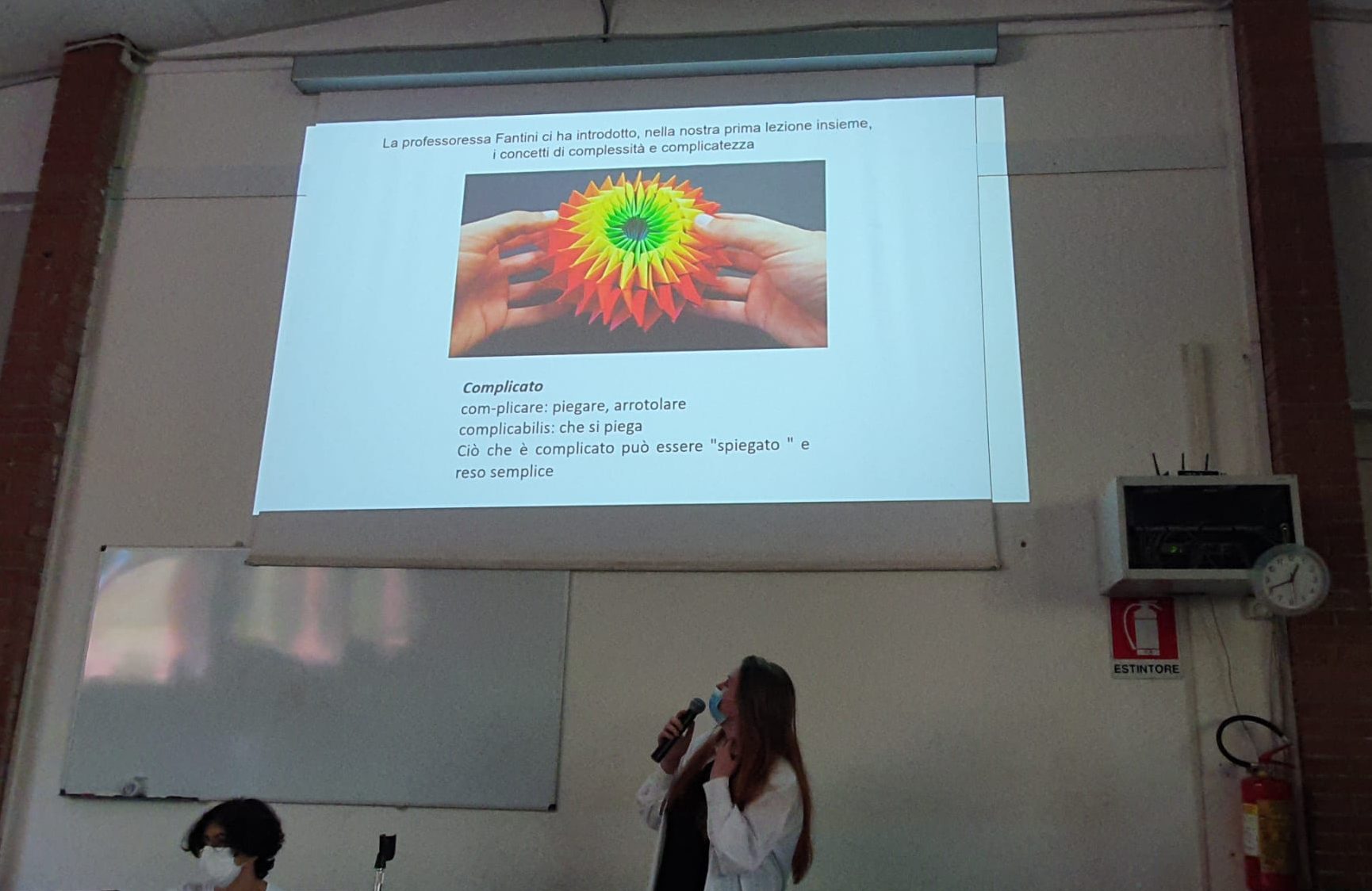

Starting by reflecting upon the difference between something that is “complicated” and something that is “complex”, students were introduced to the physics of complex systems and their main “words”. The following interactive lessons focused on peculiar characteristics and properties of these systems, such as irreducibility, circular causality and unpredictability, with references to complex systems encountered in everyday life like flocks of birds, anthills or clouds. At the same time, the writing and narratological techniques were presented through the reading, analysis and commentary of short stories. A distinguished example from Italian literature was investigated: Italo Calvino’s “Palomar”. In this collection of stories, various elements of complexity can be traced, and a critical reading of some of them made it possible to explicit how Calvino manages the intertwining between the two fields: the scientific and the literary.

In the second part, students were divided into groups and attended the writing workshop (led by the literature and history teachers). The teachers assigned each group a specific context in which to set the story, that was represented by a complex system, s7chvas an anthill, a cloud, a flock of birds, a fluid or a nest. During the workshop, the teachers constantly discussed with each group how the narrative should address complex concepts while respecting the narratological constraints. For narratological constraints, we mean that students were asked to use different kinds of narrative sequences (reflexive, dialogues, descriptive) as well as to elaborate on the duality between two main characters, where “the other” has the function to question the balance of protagonist condition, through their words.

In the second part, students were divided into groups and attended the writing workshop (led by the literature and history teachers). The teachers assigned each group a specific context in which to set the story, that was represented by a complex system, s7chvas an anthill, a cloud, a flock of birds, a fluid or a nest. During the workshop, the teachers constantly discussed with each group how the narrative should address complex concepts while respecting the narratological constraints. For narratological constraints, we mean that students were asked to use different kinds of narrative sequences (reflexive, dialogues, descriptive) as well as to elaborate on the duality between two main characters, where “the other” has the function to question the balance of protagonist condition, through their words.

Engaging in the difficult translation process from the scientific language to the narrative had three main results. Firstly, students experimented and learned how to balance systemic and analytical thinking with imaginative and creative one. Secondly, the physics of complex systems played the role of "scaffolding" to reformulate urgent questions related to the search for one's own identity in a dynamic relationship between "I" and "we” (between individual and collective). Moreover, the activity encouraged students’ critical reflection and the management of their epistemic emotions, grasping their nuances without polarising them into positive and negative emotions.

Last but not least consideration: some beautiful pieces of science-related stories were made. So, let’s conclude by looking at three excerpts from students’ stories.

After a long journey, Joy reached his destination. Stunned by the vision that was presented before his eyes, he could not believe he was so high. He let his gaze wander over all those small and different subjects that were below him, not knowing where to focus his attention. Then he recognized the thick foliage of the oak, his oak, and further down, he saw it, he saw his house, and in front of that vision, he was amazed, almost speechless; to anyone, it might have looked like a simple tangle of branches, but to him, that was the result of his own commitment, of his own effort. He could even see his mother resting, the small fruits hanging from those fragile leaves of the branch that supported his nest, the branches of different sizes coming together almost as if they were one big body; he was amazed to notice the complex plot that had been created, and he realized that, from within that intricate labyrinth, he had never seen everything that he now had the opportunity to observe. [...] Joy was so concentrated that he didn't notice the passage of time; when he raised his eyes from that dense interweaving that he had created, he noticed that the sun had now disappeared, giving way to a dense expanse of stars, among which a huge ivory-coloured sphere stood out. Every night he saw it up there, imperturbable, he admired it, enchanted by its beauty and by the sense of inferiority and helplessness he felt in front of that vision. How high can it be? How far does it go? What can you see from up there?

From the story “the eyes of the moon”

==================================

He looked at the water. Miles and miles of dark, flat, still water. He saw a bird, he couldn't tell which it was; it touched the surface of the water for a few fractions of a second before rising again towards the sky. Then he saw a fish, like himself, cut the same surface and dive right back. He thought that the birds had an opposite view compared to the inhabitants of the sea who, on the contrary, were forced to look at the world from below. Two opposite perspectives look at the same world, both aware of the existence of the other but unable to understand each other. He would have loved to know how to fly, to have the opportunity to observe everything from above. He often wondered how many things could be captured from that perspective, details that were overlooked by anyone and which instead, observed from up there, could have seemed something extraordinary. He was a fish, never able to float, destined for an existence on the bottom, at that moment he only wanted to be able to overturn his nature and get to know the other half of the world.

[...] That things don't have a unique nature, but change according to the eyes, the light under which they are looked at was clear. He looked at the moon and wondered if he felt everything he was feeling, if there was someone on the other side watching him and, while his mind formulated a thousand other questions, all his thoughts stopped in a fraction of a second, his head he lightened up. An oxymoron, sun and moon, light and dark, surface and depth, two curved lines destined to always have a meeting point, the natural correlation of two parallel universes.

From the story “the other half of the world”

==================================

Evidently the conversation is proceeding, but I was left with the swallow's reaction, after learning that it was possible to be alone. For me it is obvious that some animals live alone, that solitude is imprinted in their nature; like when we see a fox and a wolf: the fox doesn't have a group to which it can be associated, we recognize it for itself, for its cunning, its fawn fur. Instead, one of the first thoughts we associate with the wolf is her pack, like a flock to a swallow. Yet it is not so obvious. A bird like the swallow that throughout its life has been used to living in a group, to respecting rules, to having to share everything, that finds itself discovering that it can live alone, that if there is the possibility of being able to survive and even much more for another bird similar to it, maybe even for itself.

[...] Finally I guess she gathered some courage, because I hear her let out a peep: Hey, sorry to bother you again, but I need to know. How did you learn to be alone? The answer comes quickly, a caw that interrupts the silence, as if the magpie knew that sooner or later that question would come and had already prepared the answer: So you would like to be alone, huh? - she replies - I've been alone since I learned to fly, freedom and light-heartedness are my daily life, relaxing under the shade of the trees, enjoying the days as they are - continues the magpie with a very pedantic tone.

[...] How could the swallow, accustomed to living in "society", abandon everything and go away alone? Swallows have always found themselves in flocks, in a group, perhaps this is their destiny, what nature has reserved for them. What if it were the same for men? On the other hand, man is a social individual; an oxymoron highlighted by the wills in continuous opposition to each other. In every person, there is a swallow and a magpie, and we probably just need to have the audacity to want to know both, to learn to accept life in society, but also be aware of our individuality. Perhaps this is exactly what the swallow did. She has become aware of her uniqueness, aware that she is no longer just a bird in the flock. - And now that I know, will I be able to survive? - asks the swallow - maybe not, or maybe yes. I will never know. Maybe one day, she will decide to do it, and fly away. But for now, I think she's decided to return to her herd.

From the story “Flying thoughts”

What’s an “open school”? What does it mean to open the school system to the world and vice versa what does it mean to bring the world into schools? What it needs to be “opened”? Buildings, activities, people, disciplines, schedules, programs?

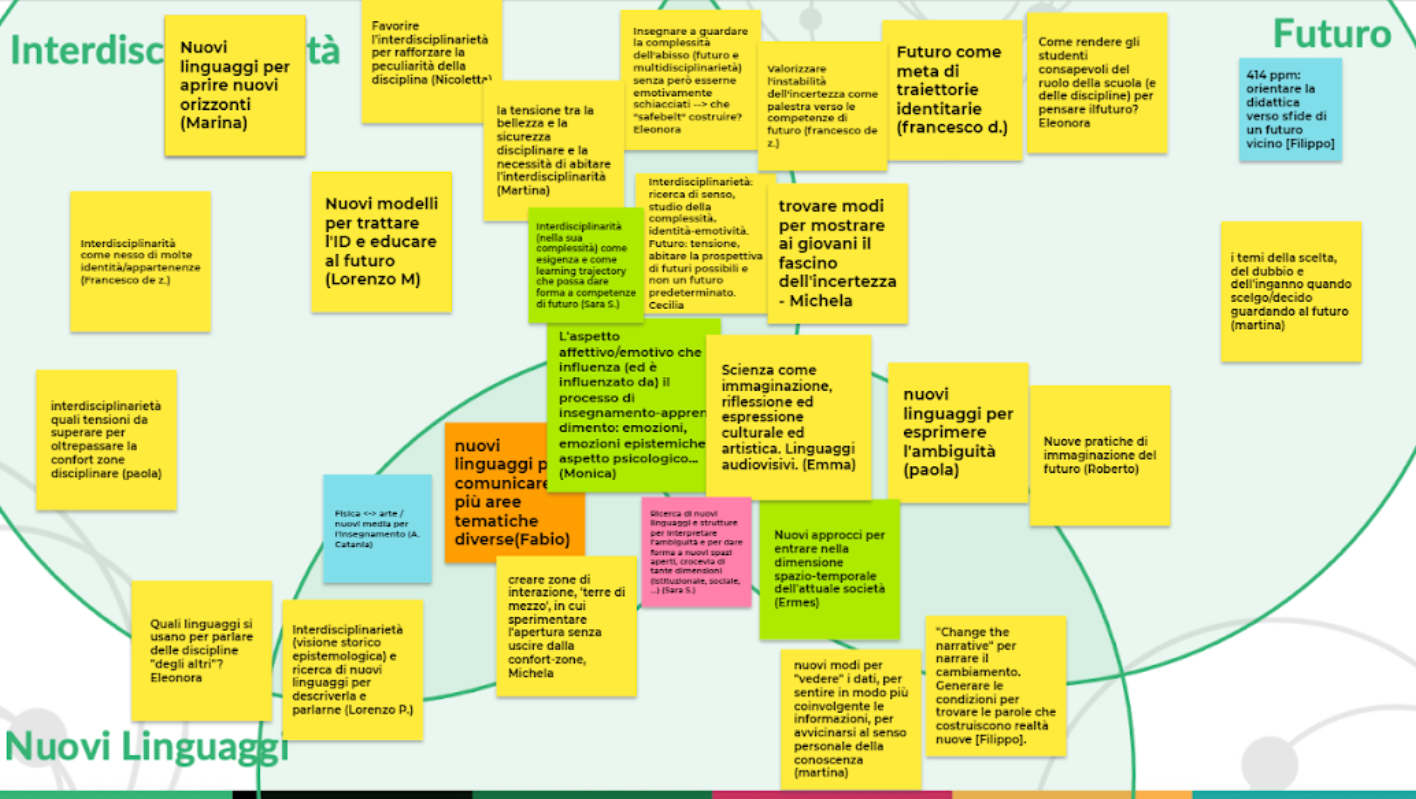

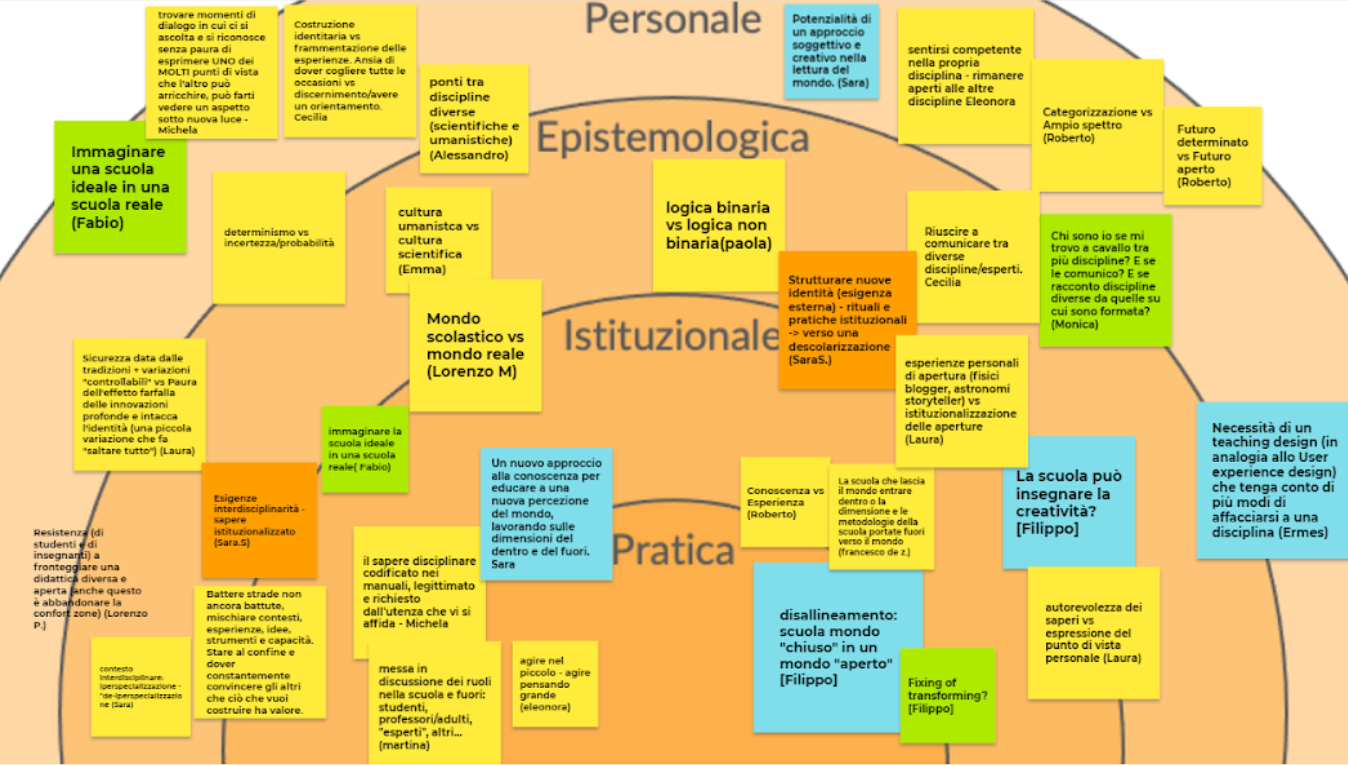

On November the 16th FEDORA invited people with very different backgrounds, skills and visions to take a break from the world frenzy and get together in order to reflect on those questions and get inspired by each other personal experiences.

As defined by the EU, Open schooling aims to support a range of activities based on collaboration between formal, non-formal and informal science education providers. This is why didactics researchers, teachers, philosophers, mathematicians, science communicators, videomakers, language experts, bloggers and other professionals joined online at FEDORA’s "Italian Open schooling Kick-off meeting” with the purpose of forming a network that will work together to design and implement “open schooling” activities and projects. These will fit with FEDORA’s main themes: interdisciplinarity, future and new languages.

The European project SEAS - Science Education for Action and Engagement towards Sustainability, from which FEDORA inherit some learnings and frameworks, identified among “open schooling” characteristics the willingness to make schools centres a model for a new idea of society and vehicles of social promotion and innovation. FEDORA, like SEAS, believes that schools should be a vehicle for change. But which kind of change? Participants reflected on four different levels [O’Brien and Sygna, 2013]: practical, institutional, epistemological and personal.

Three different projects (in progress or just finished) are the result of a reflection of this kind:

But that was just the beginning! Between January and May, specific meetings for schools wishing to deepen tools already implemented and other meetings for the exploration of new activities will take place.

The network will meet again to share their experiences on FEDORA’s second open schooling meeting that will be held on June. Stay tuned!