Science is often a driver to help solve complex problems and there lies a huge potential to increase futures literacy of teachers and students worldwide via science education. Many science curricula already contain elements of future skills like problem solving, critical thinking, creativity, systems thinking. Adding specific future skills into the mix, like agency belief, time perspective, openness to alternatives and concern for others, will enrich science education and prepare students for tomorrow.

In August 2022 FEDORA launched its Manifesto for Futures-oriented Science Education. It containes 10 recommendations to set the tone and foster futures-oriented discussions in diverse spaces, especially in schools. They derived from a selection of relevant insight that emerged from FEDORA’s preliminary studies and can be used as a starting point to update your current science curricula and lesson plans.

The following are some examples:

We often talk about the future as if there is one fixed future. But there are many futures possible. That’s why we use the plural in Futures Thinking.

To what extent do the activities and exercises in your science curriculum and lesson plans help pupils to think in more than one possibility and solution?

To become open and aware of multiple possible futures, you will have to scan the world around you in a very broad way.

To what extent do the activities and exercises in the toolbox and the toolbox itself facilitate in using a broad range of sources to find signs of change?

The future is not here yet and there are many futures possible. Involving yourself in futures thinking related activities will help you to be more comfortable with the feeling of uncertainty and ambiguity, as there is no ‘right’ answer.

To what extent do the activities and exercises in your science curriculum help out in feeling more confident in handling uncertainty and allowing multiple solutions?

Thinking in multiple future scenarios requires the ability to open up your imagination to the max. Out-of-the-box thinking is needed to imagine the seemingly impossible.

To what extent do the activities and exercises in your science curriculum and lesson plans stimulate a very open and divergent approach to imagination and fantasy?

To make sure that futures thinking is not only used as a source of inspiration but also as a way for activation you will have to reflect on your preferred future. From the multiple futures out there, which one would you like to see happening and why?

To what extent do the activities and exercises in your science curriculum and lesson plans help users to reflect on their preferences and make a substantiated choice?

FEDORA’s research further investigated students’ concerns and uncertainty towards the future. Some crucial guiding questions were: How do young people perceive their personal and global futures? How do they imagine the role of science and technology in those futures? How can science education foster students’ futures thinking and agency?

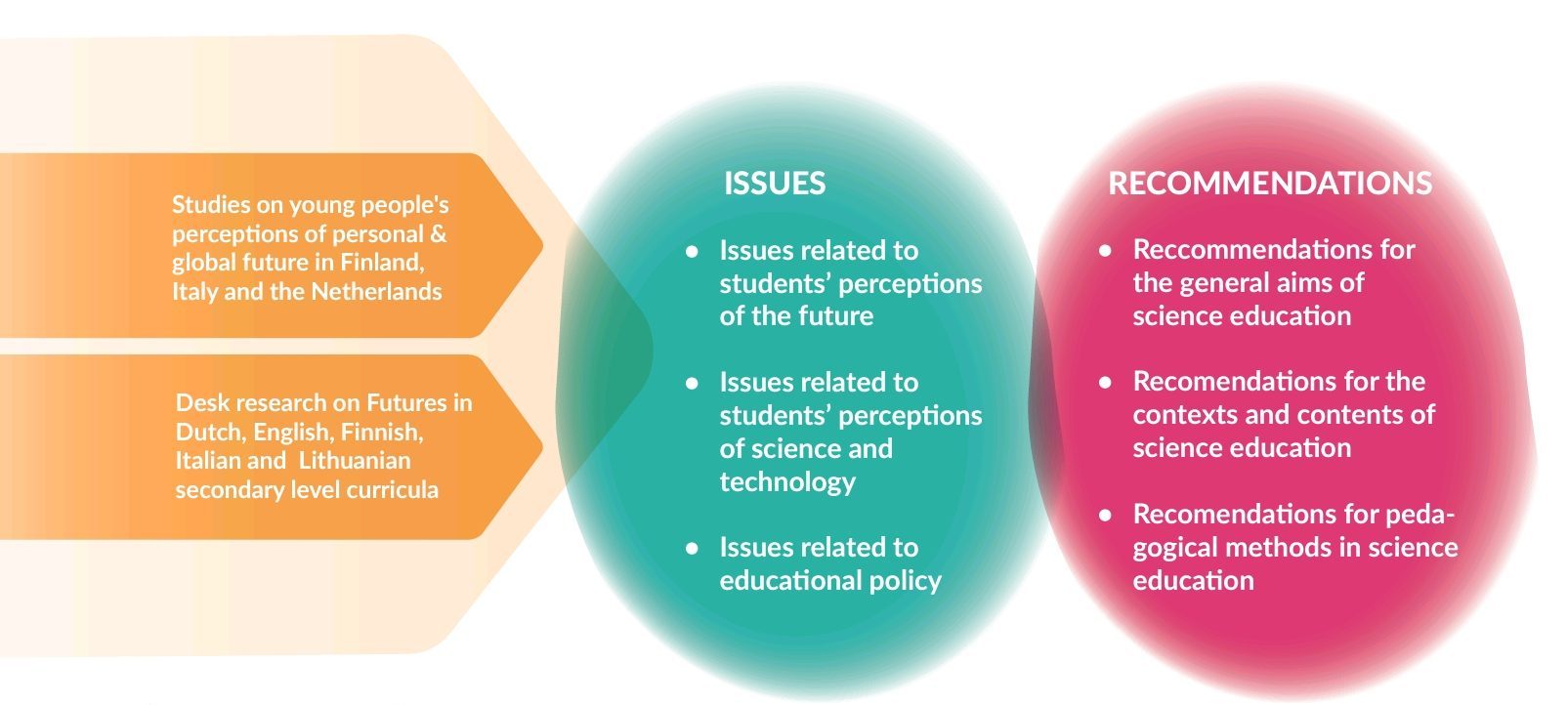

Led by the University of Helsinki, five studies on young people’s perceptions of the future and one study on European curricula were conducted. The empirical studies on students’ futures thinking focused on their sociotechnological images of the future, hopes, fears, perceptions of agency and tendencies for polarisations and “bubbles” in their thinking. The curriculum study identified explicit and implicit links to futures thinking skills in European science curricula for secondary schools.

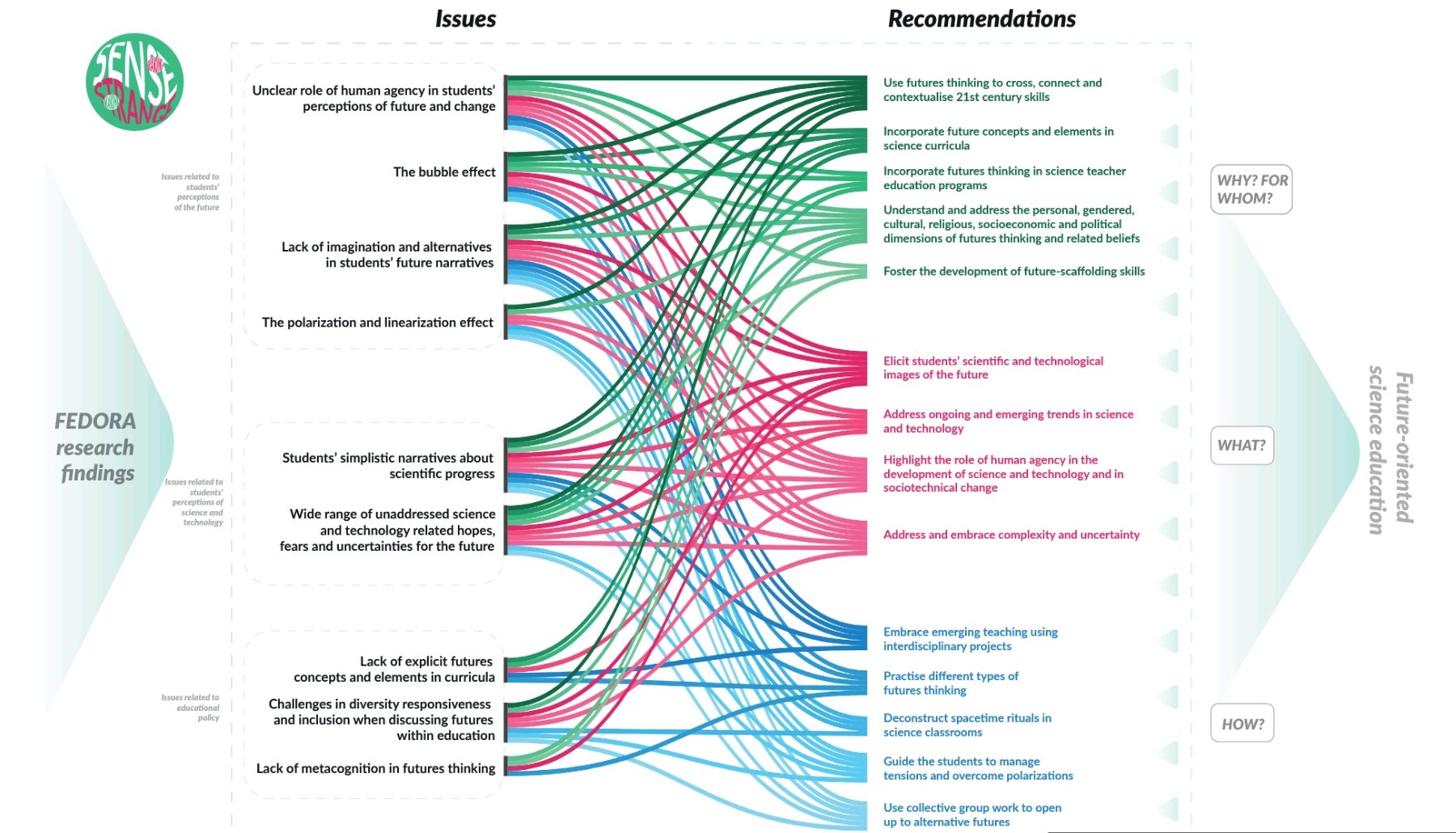

Through these investigations, nine key issues to be addressed by future-oriented science education were identified. They involve students’ perceptions of the future, students’ perceptions of science and technology and educational policy. Based on the findings of the studies, we propose a set of 14 research-based recommendations to futurise science education. The recommendations aim to address problematic issues and limitations in students’ futures thinking, connect futures thinking skills to scientific and technological skills and knowledge, and address related aspects of educational design and school culture. The recommendations are grouped into three categories:

These results aim to constitute a groundwork for future-oriented science education that provides students with tools for deeply connecting with and finding agency within their personal and global futures.

The following infographics illustrate the process leading to the research-based recommendations and how the recommendations correspond with the identified issues in a variety of ways. As a framework, the recommendations provide a broad and deep perspective on how to futurize science education. Both the issues and the recommendations offer several openings for research agendas and projects.