Unfortunately, our educational systems are rarely involved in a discussion or reflection about those issues. They often remain rigid and do not appear able to keep the pace of change. As a result, a serious gap emerges between what the traditional educational organisations are producing and what society requires.

In order to innovate science education and equip young people with the skills needed to address current and future societal challenges, FEDORA worked at identifying the limits of discipline-based knowledge organisation and proposing new ways to address them through interdisciplinarity. The guiding questions addressed were:

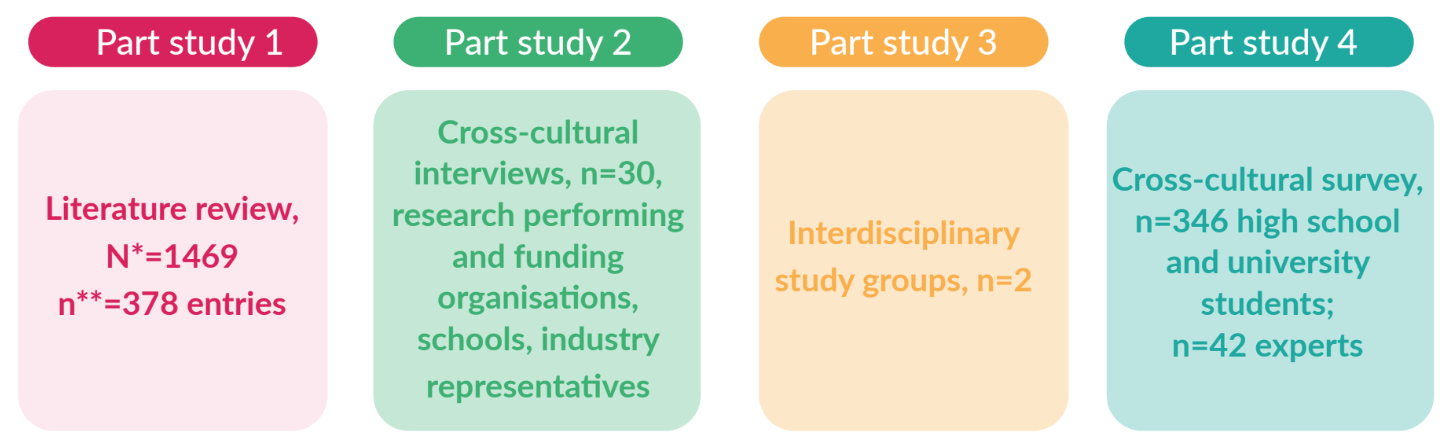

Led by Kaunas University of Technology, four-part studies were conducted:

Overview of the 4 Part studies.

Research findings from Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Lithuania, the United Kingdom.

N*= Total No. of entries, n**= Selected No. of entries for analysis

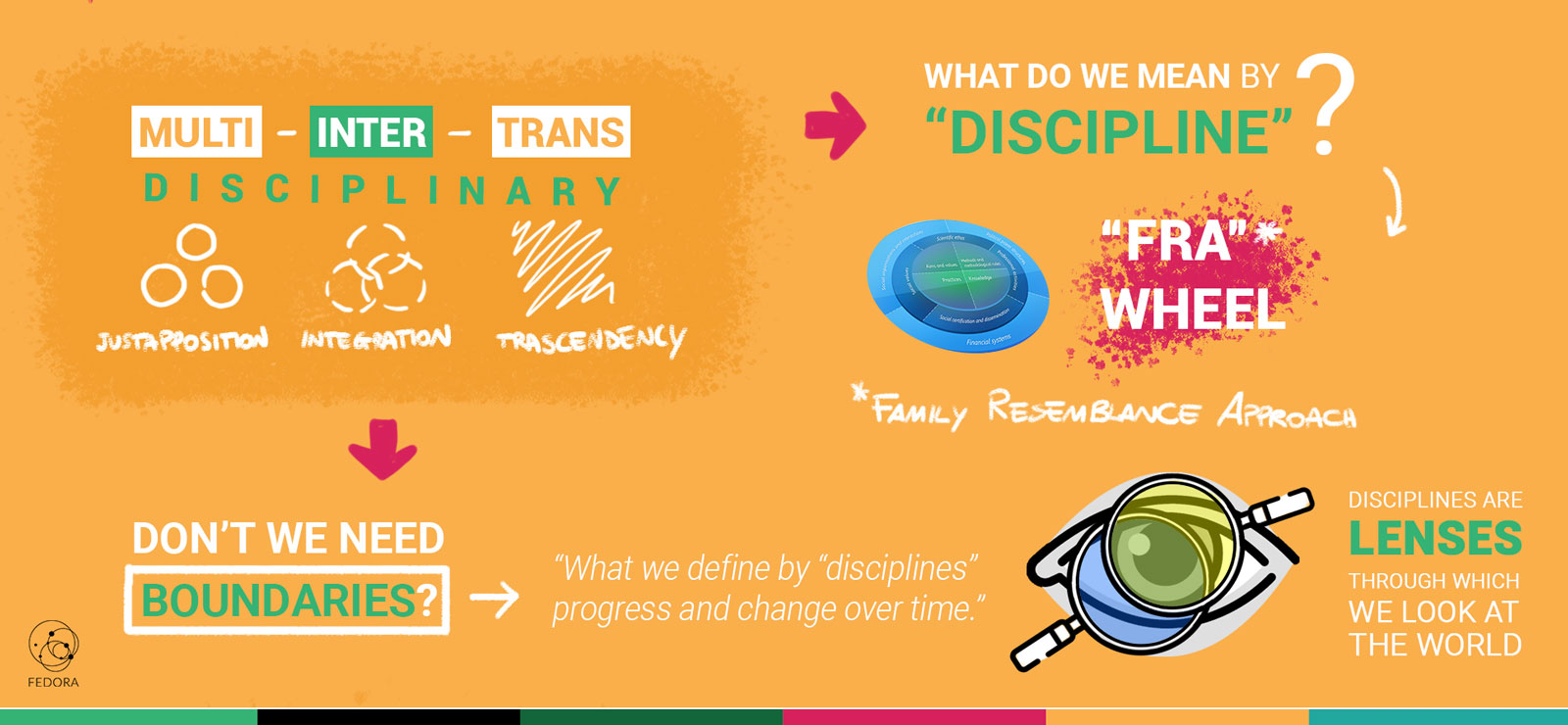

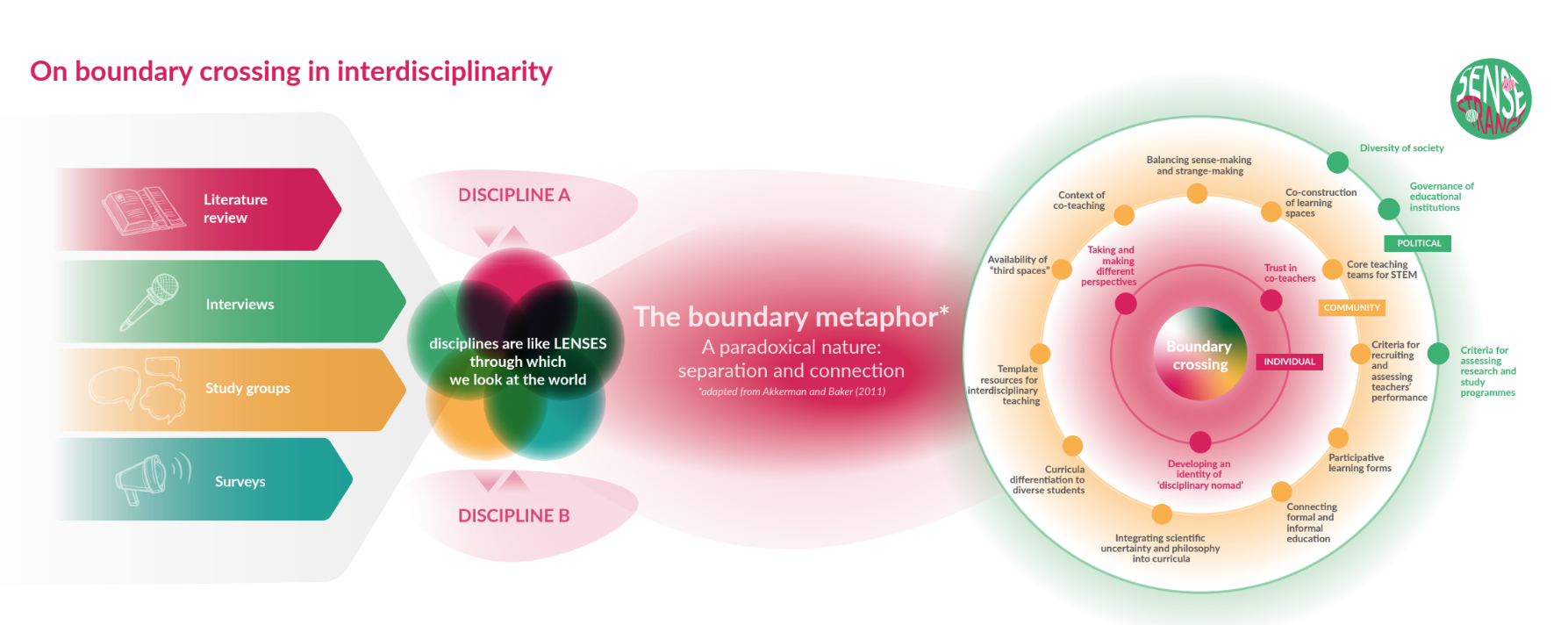

Two words, and the metaphors attached to them, are crucial. The first one is the metaphor of the boundary (Akkerman & Bakker, 2011) that was used to model interdisciplinarity and its “paradoxical” nature: boundary both separates and connects. Analogously, interdisciplinarity blurs and redefines disciplinary identities and requires managing the equilibrium between “sense-making skills” – systems, critical and analytical thinking- and “strange-making skills” – creative, imaginative and anticipatory thinking. The second is the metaphor of the barrier that we used in interpreting the results and that connotes a separating obstacle; differently from the boundary, barriers do not have a characteristic of connectivity and cannot be easily crossed and demand systemic changes.

Gathering inputs from a variety of voices, three “shared narratives” arose from preliminary findings:

An idea that produced a great resonance in the study group was realising that interdisciplinarity in STEM means more than managing tensions, it also considers managing balance. What are the tensions that we are talking about? Tensions between belonging and not belonging, defining or negotiating meanings, going in or out of a comfort zone, zooming in and zooming out -from details to big pictures and vice versa.

By managing balance, we mean managing a particular kind of equilibrium between what we call “sense-making skills” -systems, critical, analytical thinking- and “strange-making skills” -creative, imaginative, anticipative thinking.

Informed by the papers of Akkerman and Bakker on boundary crossing and objects, and by the Family Resemblance Approach, developed by Sibel Erduran, Zoubeida R. Dagher and colleagues, we framed the space where we started our exploratory journey.

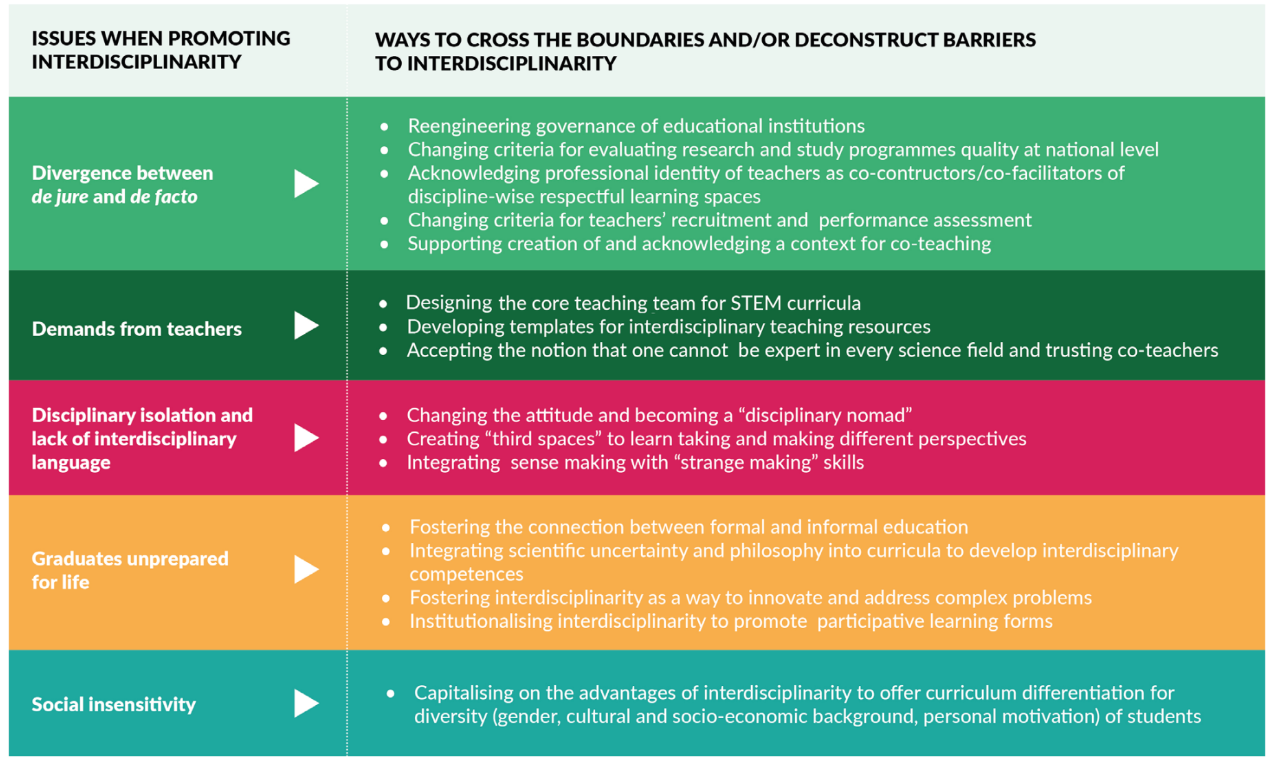

The final outcomes of the studies revealed five main issues that appeared as boundaries or/and barriers in formal educational contexts: 1) Divergence between de jure and de facto in educational policies and practices, 2) Extensive demands from teachers, 3) Disciplinary isolation and lack of interdisciplinary languages, 4) Graduates unprepared for life 5) Social insensitivity.

Issue 1 stems from inconsistencies between national regulations and institutional practices, obstructing interdisciplinarity, institutional competitiveness and social impact. They are most perceived through the arrangements at the political level, such as governance mechanisms in educational institutions and national criteria for research evaluation and funding, as well as accreditation of quality assessment of study programmes.

These discrepancies account for at least three subsequent issues at the community or institutional level.

Issue 2 relates to excessive workload and demands from teachers and researchers. Moving towards interdisciplinarity threatens teachers’ authority and self-confidence and demands extra time in connecting different disciplines. Disciplinary isolation through departments at research performing and research funding organisations, as encoded in issue 3, creates a ‘silo’ effect. It constructs social, cultural, and institutional barriers as well as cognitive and epistemological boundaries to interdisciplinarity. A closed culture of disciplinary communities further strengthens individual and community identities through symbolic languages, representations and communication practices. Ultimately, this leads to issue 4: graduates unprepared for working life and beyond it. A disciplinary approach to knowledge organization is seen as erecting systematic barriers to developing transferable skills needed by the labour market and practical life, e.g. applying conceptual knowledge to practical problem-solving, self-confidence and efficacy, existential skills, teamworking, life-long learning skills, futures thinking skills etc. Current education is perceived as failing to develop these skills, and lack of cooperation between experts in STEM and social sciences is seen as a barrier to innovation development.

Finally, issue 5 brings focus on the interrelation between ongoing changes at the societal level and efforts to address them at a community level. Rote learning, standardized tests to monitor students’ progress, and academic achievement-driven culture are criticized for failing to respond to the growing diversity of society. Intersectionality of students’ race, ethnicity, gender, disability and other social categories decreases the chances of socially excluded or underrepresented groups to pursue education in science.

FEDORA developed a framework for aligning science teaching/learning to the modus operandi of R&I. The following table summarizes the strategies that might be implemented to address each of the issues presented above, that means ways to cross boundaries between disciplines or deconstruct barriers to interdisciplinarity.

Those recommendation can be enacted at three levels: individual, community and political.

At the political level, re-engineering governance and changing institutional processes must take place: key performance indicators, funding formula, adding qualitative criteria of staffing, coordination, performance assessment, workload allocations have been previously identified as the prerequisites to ensure the sustainability of interdisciplinary courses. Remodelling criteria for evaluating research must also occur: the guiding point is not “ease of evaluation” but the importance of the research problem and impact on society that the research will produce, which is promoted by strategic programming documents at EU and national levels.

At the community level, in particular in research institutions, human resource management practices have to be revisited: adding qualitative criteria to quantitative ones in the criteria of staffing, coordination, performance assessment, and workload allocations have been recommended by prior research. Emphasis on collaboration at the institutional level may contribute to maintaining teacher teams with the mindset of co-ownership of interdisciplinary courses and securing a stable core teaching team with a mindset of co-ownership of interdisciplinary courses. Developing supporting materials may add to the effects of institutional changes.

At the individual level, a coping strategy of a “disciplinary nomad” and the development of a common interdisciplinary language, may facilitate overcoming cognitive and epistemological barriers and enacting interdisciplinarity.

The recommendation above leads to the community-level approach again, indicating the need to establish a “third space”, be it a physical or a virtual one, that is free of disciplinary metalanguage and symbols to enable interdisciplinarity.

The following infographics summarizes FEDORA's interdisciplinarity in science education framework.

Barrier: a fence or other obstacle that prevents movement or access. -Oxford Online Dictionary

Disciplines can produce epistemological and cognitive barriers since each discipline has its own epistemology, in terms of aims and values, practices, methods and ways to systematize knowledge. Hence, professionals and their disciplinary identities can emerge in interdisciplinary contexts as obstacles.

Interdisciplinarity is a very timely and relevant theme, but institutions do not seem to provide real guidelines to manage inter-multi-trans-disciplinarity. Moreover, the problem of how to foster inter-transdisciplinary or trans-institutional collaborations and connect educational contexts to the job realm remains open. In many cases, the creation of inter-trans-multi-disciplinary collaborations is in fact hindered by evaluation/legitimation/accountability criteria in the institutions, together with specific funding systems. Furthermore, academic and school culture, more or less implicitly, seems to produce a “culture of closure”.

What is a culture of closure and how does it relate to barriers?

A culture of closure is created, for example, by valuing more dissensus and specific forms of disciplinary expertise rather than abilities like consensus building, and the capacity to legitimize others' roles or expertise in multi-/inter-disciplinary teams.*

We found that cultural aspects- within institutional domains -manifest themselves as perceptions that become implicit assumptions, rituals, and habits of mind and hence emerge as emotional barriers. Emotional barriers can be represented by the feeling of discomfort or a sense of insecurity about one’s own role and expertise. These feelings might be due to factors characterizing the community’s attitude and what we called the “culture of closure” and by asymmetries/differences in the roles that close contexts “naturally” reproduce. They can also derive from the clash between contrasting beliefs that act implicitly.

About “boundary people”

A similar deep sense of discomfort may be felt by “boundary people” within close disciplinary communities. People hardly possess multiple domains of expertise in one individual, and the main strategy cannot be to enlarge the expertise to other disciplines. Thus, boundary people must work in a team rethinking themselves from the epistemic point of view, experience new roles in the development of knowledge in a team of experts and relate to her/his own and others’ expertise in a different way.

However, interdisciplinary teamwork is not only difficult at the epistemic level. It is also challenging at a ground level due to the lack of cognitive skills that seem not so relevant in disciplinary contexts, like:

In disciplinary closed communities, symbolic languages, representations and communication practices are developed. In order to collaborate and “negotiate” in interdisciplinary contexts, it is necessary to address the need to find a shared language (tools, words, structures...) and the obstacles associated with this. When languages are competing, it can happen that there is little motivation to change. Moreover, finding ways to convey is strenuous, and although a set of actions is required, it goes way beyond making a checklist. It requires finding appropriate languages and effective ways to describe nonvertical expertise.

-A complete report on this topic is part of Deliverable 4.1-

*We can also name the capability of bridging, the ability to understand the cultural and social background that frames or influences one's view/perception/reaction.

Boundary-crossing mechanisms are “learning potentials'' that need to be activated.

Their activation can be facilitated if the “trading zone” is properly created or if it occurs in new contexts or third spaces, where habits are given up and the roles of participants are clear or have been made clear. New contexts can be summer schools for PhD students, like ESERA’s one, where every student thinks about the same topic but with his/her own expertise or transdisciplinary activities are carried out, like asking students to play the role of a science journalist. A third space can be, for example, locations or hubs for innovation, or even primary teacher education institutes.

Scaffolding a “trading zone” as a safe third space deserves special attention since experiencing interdisciplinarity implies accepting and managing uncertainty, ambiguity, openness, insecurity and feelings of discomfort. To scaffold a safe third space, a solid plan for discussion - a “choreography” - must be designed and consistently managed by a facilitator.

This means that, when the roles and the structure for discussion are not clearly determined by the specificity of the context itself, the principles and “rituals to embrace the ambiguity of interdisciplinarity” need to be shared and implemented. Principles may include:

Rituals may include an activity for going out and coming back to the comfort zone, inspiring creativity and converging to the personal area of expertise.

-A complete report on this topic is part of Deliverable 4.1-

Concerning moods and attitudes, three aspects can make the difference in an interdisciplinary context, and therefore, turn knowledge exchange into a pleasing experience: to adopt an “acceptance” and/or a “recognizing/valuing” mood.

Acceptance concerns a variety of dimensions:

An idea that produced a great resonance in the study group was realising that interdisciplinarity in STEM means more than managing tensions, it also considers managing balance. What are the tensions that we are talking about? Tensions between belonging and not belonging, defining or negotiating meanings, going in or out of a comfort zone, zooming in and zooming out - from details to big pictures and vice versa.

By managing balance, we mean managing a particular kind of equilibrium between what we call “sense-making skills” -systems, critical, analytical thinking- and “strange-making skills” -creative, imaginative, anticipative thinking.

Accepting the intellectual risk, embracing ambiguity and managing the equilibrium between “sense-making and strange-making skills" appear as interesting “constructs” that will be further elaborated during the second year of the project and will orient the design of instructional materials, being also the bridge to elaborate on our main research goals: to outline forms of knowledge organisation and participation that foster interdisciplinarity.

As for accepting the risk, questions like the following need to be addressed:

Embracing ambiguity is a key concept in design-thinking methodology and, together with accepting the risk, is considered a strategic skill for leadership and for becoming a successful professional (see, e.g. IDEO).

In FEDORA these constructs need to be re-conceptualized so as to orient science education to become a context to “form people able to navigate the complexity of the society of acceleration and uncertainty” (and not only to “train high performant and successful professionals”). The equilibrium between sense-making and strange-making skills is particularly interesting to be explored since it acknowledges the tension between disciplinary identities and inter-disciplinarity.

In FEDORA, disciplines and their epistemic cores are considered crucial to guide the students to make and consolidate “structured” educational experiences. Such experiences represent a solid ground that is needed to develop “sense-making” skills and from which a student can take up the process of crossing the boundaries and developing strange-making skills.